Last weekend at SBG’s annual Spring Camp, 150 people sat and listened to our traditional Sunday question and answer wrap up with the coaches. One of the students, a man my age (49), asked a question about training as you get older. He received two answers.

The first answer was from long time coach John Frankl, who told a story about an older black belt that has a tendency to protest a bit too much about the difficulties of doing Jiu-Jitsu in your 60’s. When John suggested he might try rolling a bit lighter, the man said “I know John, but sometimes they have that americana, and you just don’t want to tap!” The more he spoke, the more it became obvious how self-inflicted the ‘problem’ was.

The second answer came from long time coach, Chris Conolley. His point was different. Jiu-Jitsu, like many things worthwhile, is hard. To stick with it, to become good, you have to understand that – and tough it out. Or as coach Chris phrased it – “you have to become as hard as woodpecker lips!”

The contrast between those two answers, and the two personalities, reminded me of the two seargants in the movie Platoon. But the truth is there was no contradiction.

The kind of disfunctional training and attitude coach Frankl was talking about wasn’t “tough”, it was stupid. And the kind of mindset coach Conolley was talking about wasn’t stubborn, it was Stoic. Understood properly, there was no disagreement.

This brings me to coach Fitz, and the necessity of surpassing.

Surpass: Making sure our students exceed our own accomplishments, is, if you’re a good functional Martial Arts coach, always the end goal. As you age, that process can be a valuable journey not just for your students, but also your own ego.

When I first began teaching, I had no students that could consistently beat me. In nine out of ten, twenty, or a hundred matches, I would probably get the tap. Unless I was working with a professional fighter like Randy Couture, or one of my own coaches like Chris Haueter, I was usually winning. You can get used to that.

I am now, at the time of this writing, 49 years old. If I stopped teaching all together, abandoned my family, and dedicated myself to nothing but training for the next year, I’d still have zero chance of ever winning at the Mundials (BJJ World Championships). I am simply too old. My Jiu-Jitsu feels better than it ever has, and I have little doubt that the BJJ player I am now would make easy work of the BJJ player I was 17 years ago, as a young black belt. But still, to ascend through the brackets of the Mundials is a process that’s left to the twenty and young thirty year olds.

Ask yourself a question. As a BJJ coach, would you ever want to create a world champion? Would you want to produce an athlete that could not just place, earn a medal on the stand at the Mundials, but actually win? If your answer is yes, then consider for a moment that once you get close to my age, or even within ten years of it, you will, by definition, have to be capable of creating athletes that can consistently, in nine out of ten, twenty, or a hundred matches – beat you.

If you’re not producing athletes like that, you’re not going to be capable of creating athletes that can win world championships.

It stands to reason then that your job as a BJJ coach who is good at your job, is to make people who can consistently tap you out. And if your own ego can’t come to grips with that reality, then your own ego will be the thing that prevents you from ever becoming a good BJJ coach.

It’s an absolutely perfect system. Embrace it.

This doesn’t mean I am not going to try my best, at times, to give my black belts a hard time. You must always strive to better yourself as well. But it does mean that if throughout those battles, I still find myself on the winning end the majority of the time, I need to take inventory and find out what I am doing wrong.

As a father too my end goal with all of my five children is to see them exceed whatever success I have had. Advancing my families standing, through the endorsement of values like education, ambition, and hard work, is what it’s all about. And again, I try to do that not just through my words, but through my actions. I cannot expect my children to ask more from themselves than I’ve taught them to do through example.

“Professor Lewis M. Terman demonstrated that success, if not intelligence, ran in families. Whether it was genetic or environmental or, more likely, both, is impossible to divine from his study. Unquestionably, however, certain families primed their children for success in life and others sent them off with a handicap. The single greatest determinant of success was education. The homes of the most successful child subjects typically had at least a five-hundred book library. Good grades and extracurricular activities were thought of as a norm and were actively encouraged. In these families, whether a son, or in most cases, a daughter should go to college probably was never an issue, even when paying for it was. Families were important in other ways. The Terman researchers found that the families of most of the highly successful subjects were close and affectionate and the role of the father was a surprisingly strong one. The fathers were not passive and they did not leave child-rearing exclusively to the mother. Success was expected.” – William A. Henry III

Affectionate, loving, close, these are all commonalities, along with the presence of strong fathers, that researchers have found present within successful families. But none of those things mean coddle.

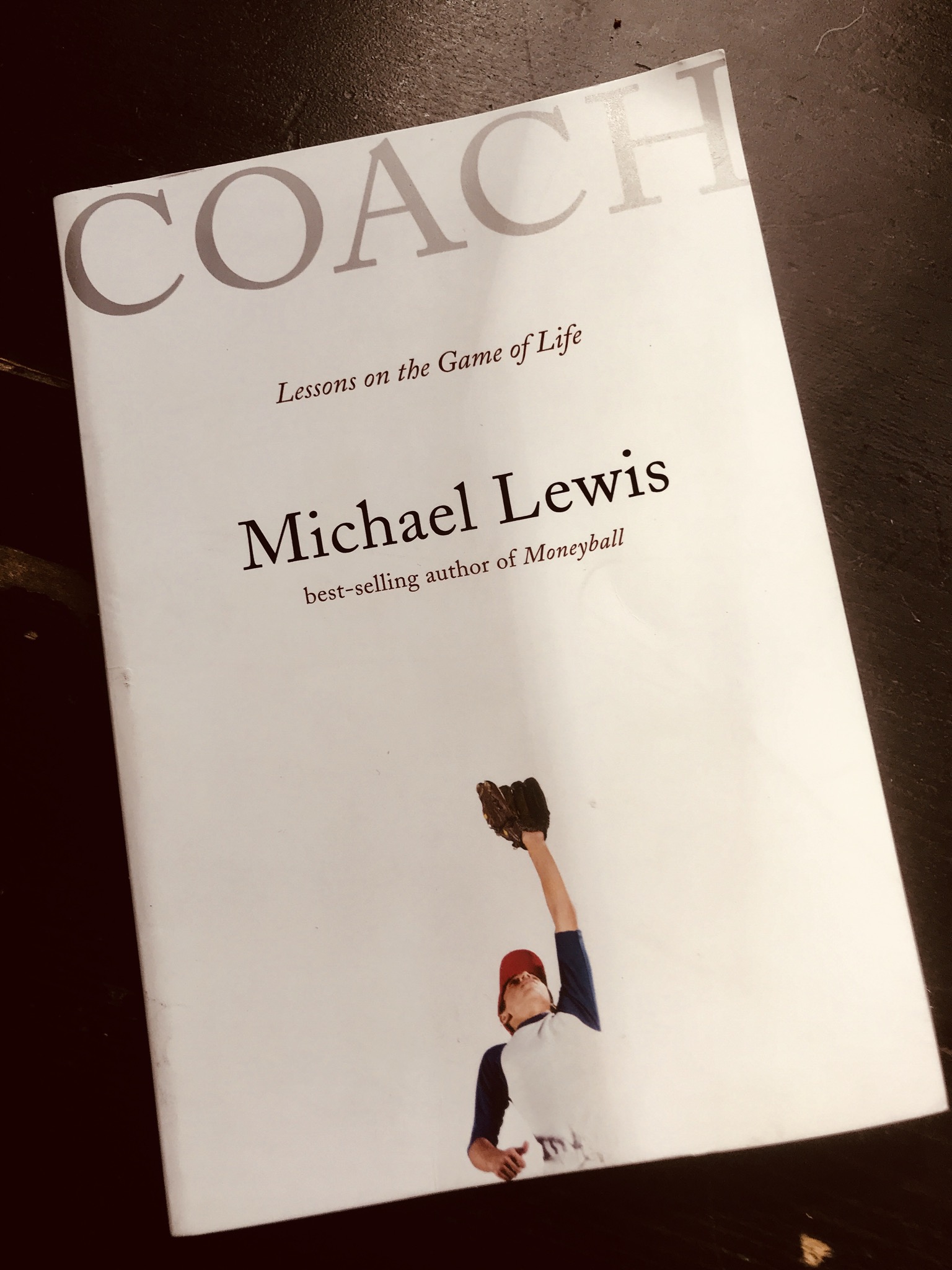

In Michael Lewis’ short book, Coach (I recommend everyone read it); which was a tribute to his own childhood coach, Billy Fitzgerald, aka: Coach Fitz, Lewis follows Coach Fitz’s career from the time Lewis was his student, to present day. Present day wasn’t looking so good.

Listen to the great lesson that Lewis, a successful writer if ever there was one, took away from his coach:

“What he knew – and I’m not sure he’d ever consciously thought it, but knew it all the same – was that we’d never conquer the weakness within ourselves. We’d never drive the worst of ourselves away for good. We’d never win. The only glory to be had would be in the quality of the struggle.

I never could have explained at the time what he had done for me, but I felt it in my bones all the same.”

Those were not the lessons of an authority figure that was more interested in being liked than imparting truth. Those are not lessons that come from egalitarians who fear and detest competition, who embrace romantic Marxian babble about the invariable blamelessness of the unaccomplished, who lie, and despite all evidence to the contrary, pretend that talent, in all its multitude of forms, is evenly distributed, and that everyone, despite distinctions in effort or attainment, deserves the same outcome. No – Coach Fitz cared too much about his students to shirk his responsibilities. Instead of focusing on his own selfish impulses to be liked, instead of approval seeking, coach Fitz was doing his job. Coach Fitz was coaching.

The sadder part of the story, which takes place towards the end, is how the helicopter parents of our current, more prosperous generation, interfered with his mission.

When Michael Lewis returned, as a grown man and father to his own children, Coach Fitz relayed the following:

“They don’t get it. But most kids don’t get it. The trouble is every time I try the parents get in the way.” By “it” he did not mean the importance of winning or even, exactly, of trying hard. What he meant was neatly captured in a sheet of paper he held in his hand, which he intended to photocopy and hand out to his players, as the keynote for one of his sermons. The paper contained a quote from Lou Piniella, the legendary baseball manager: HE WILL EVER BE A TOUGH COMPETITOR. HE DOES’T KNOW HOW TO BE COFORTABLE WITH BEING UNCOMFORTABLE. “It” was the importance of battling one’s way through all the easy excuses life offered for giving up. Fitz had a gift for addressing this psychological problem, but he was no longer permitted to use it. “The trouble is”, he said, “every time I try the parents get in the way.” …

…”Look,” he said. “All this is about a false sense of self-esteem. It’s not bestowed on kids at birth. It’s not earned. If I were to jump all over you today, you would be highly insulted and deeply offended. You would not get that I cared about you.”

…An invisible line ran from the parents’ desire to minimize their children’s discomfort to the choices the children make in their lives. A week later, two days before the start of regular season, eight players got caught drinking. All but one of them – two team captains, two members of the school’s honor committee – lied about it before confessing under duress. After he’d handed out the obligatory, school-sanctioned two-week suspensions to eight players, Fitz gathered the entire team for a sharp, little talk. Not two days ago he had the patience for a long sermon, about the dangers of getting a little too good at displacing responsibility. (“You’re gonna lose. You’re gonna have someone else to blame for it. But you’re gonna lose. Is that what you want?”) Now he had only the patience for a vivid threat: “I’m going to run you until you hate me.” The first phone call, an hour later, came from the mother of the third baseman, who said her son had drank only “one sip of a margarita,” and so shouldn’t be made to run. She was followed by another father who wanted to know why his son, the second baseman, wasn’t starting at short-stop instead.“

Making sure our students and those we mentor surpass our own achievements, become better than we were, take the art and science farther than our generation had – doesn’t come as a result of us mollycoddling them. It doesn’t arise out of our desire to be “friends” with them. No – helping those that come after us become better than us is a job that requires us being too honest and too concerned with their well-being to do any of that.

If we want to produce champions on the mat, and in life, then we want those in our care to train as smart as coach Frankl rightly teaches, while being tough as woodpecker lips, as coach Conolley rightly preaches.

The SBG way – is to do both.