An essay on the belt system of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu’ originally published in Sunday, March 12, 2006

One of the more controversial aspects of Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu is the colored belt system.

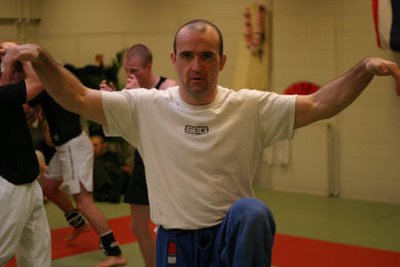

For those less familiar with BJJ, let me explain that the BJJ belt system remains (especially within the SBGi Association), performance-based. What that means is that if someone has a purple belt, then they should be able to roll with other purple belts of the same age and similar weight, and be competitive. The belt itself is simply a visual reminder of this skillset.

That is a very different form of measurement as compared to most traditional martial arts, which being based on dead patterns and choreographed two-person demonstrations are not an indication of any practical skills, which relate to actual fighting.

To be honest, the only other martial art which I can think of that has kept to a functional form of measurement when it comes to belts is Judo. However, Judo being far more popular then BJJ, has a wider margin of error when it comes to what the belt may or may not indicate in terms of skill. BJJ is still a fairly tight community, and it would be next to impossible to maintain the illusion that you were a brown or black belt in BJJ, if you were not. The reason for that is, of course, the Alive training.

Although not everyone competes publicly, everyone does roll against fully resisting opponents. As such, you cannot fake being good at BJJ anymore than you can fake being good at speaking Spanish, playing the guitar, or playing basketball. That is what gives the belts in Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu the notoriety that they hold.

So, what’s wrong with that?

Many athletes have grown a serious aversion to any form of traditional measurement or symbols. Their reasons for this aversion are valid and, if anyone would know these reasons well, it would be me. My entire career has been a sincere effort to bring people into a state of questioning when it comes to all forms of traditional measurement. That questioning was not only needed, and long overdue, it was healthy. Terms like Alive training, dead patterns, delivery systems, etc., have entered the grid of modern martial arts consciousness, and are repeated in writing and language all over the world now. Regardless of what some critics may claim, SBGi has played a major role in changing perceptions regarding what functional, healthy, and sincere training can be. That sets the stage. BJJ belts are performance-based, which makes them a completely different animal from other belt systems, certificates, or forms of measurement. That is a healthy thing. Yet, at the same time, the entire idea of attaining validation from any source outside your own self runs contrary to the whole philosophy, or underlying theme, of Aliveness & SBGi. It is a theme, which I have been a major advocate, and proponent for.

It is that seeming contradiction of ideas that creates the tension, as well as the value, which the belt system used in BJJ holds.

Observe hypocrisy:

One of things to watch for with vocal critics of the BJJ belt system is the hypocrisy. Identification with an outside measurement as a form of personal identity is of course the problem with measurement. Without that identification or attachment, the belts, or any other form of measurement, become harmless tools. That identification is the only valid argument against these types of measurements.

*(Many of you, I am sure, already realize this, but if this idea is new to you, then I would encourage you to question this concept vigorously, and think it out for yourself.)

The irony is that every individual I have ever met that was strongly opposed to the use of belts in BJJ was also clearly attached to their own form of measurement, in the sense of identification through the ego. It would not be uncommon to see the same individuals arguing for other forms of exclusivity, separation, or labels. As with all labels, it’s not the symbol that is the issue, but what is behind the symbol the moment it is used.

In other words, there is a world of difference between saying, “Who cares what belt you are“, and saying “Who cares what belt you are“, and actually meaning it. If you observe closely, you can see which is which and, to get to the latter, you sometimes have to take a journey.

That being said, there is probably no single issue with BJJ that creates more controversy than the belt system.

Why the fuss?

The fuss points to value.

The controversy points to an opportunity to learn about the self.

The hypocrisy is clear if you measure.

The interesting question then is, “What’s behind it?”.

Attraction and Aversion

These are always two sides to the same coin. Top – bottom, left – right, attraction – aversion. One is not possible without the other. See that for what it is.

Both point to attachment. Both point to a fundamental misunderstanding between the description and the described, the symbol and the symbolized.

A gift given for manipulation, a gift given from love: which has value? An endorsement given because someone is a buddy, or an endorsement given out of a sense of deep integrity for your craft; which has value?

Without judgment of others, what is behind it all for us?

Why measure at all?

The moment you begin coaching and helping others, you will be asked to measure. Let me give you a concrete example.

I love to roll. There is nothing regarding this thing we do that I enjoy more, than doing the thing itself. Teaching a seminar is fun, running a class is fun, and the ability to help others through this trade is great privilege. It has allowed me travel all over this planet, and it has created a network of wonderful people along the way.

That being said, there is still nothing I would rather do when it comes to Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu than just roll.

After a good roll it would not be uncommon for me to sit up and tell the athlete what they did that was really good, that gave me a very hard time, and what would be worth improving on. This is just a natural habit I have developed, and the reason for it is pretty simple. I have become so used to being asked, “What do I need to work on? What can I improve?” I have discovered over time that people really appreciate and want that feedback about their game. These are perfectly natural questions that you have to get used to if you plan on entering the coaching field.

Besides that daily ‘mat chat’ that occurs naturally after most rolls, there is another question which will get asked of you often: ”Where am I at?”

In BJJ terms, this is often a veiled reference to, “What belt do I think they may be?” Or, “How far from the next belt do you think I am?” Before any of us judge that question, ask yourself, “Have you ever asked a coach, or BJJ black belt that question, yourself?

Again, it is a natural question and one that you need to get used to being asked all the time if you plan on coaching.

Here is the cold reality when it comes to being a coach or teacher. Even if you focus your teaching around performance (something I try and always do), i.e. these are things you do well, these are things to work on, and you will still be asked to measure. It is part of the job, and since it arises of its own accord, I also feel it is something that we, as coaches, are responsible for dealing with in a healthy way. By that I mean we are here to serve as guides through, and within, the issue of measurement.

How do I know this to be true? Because it is what happens. Reality tells us.

If we try and avoid the issue by repression, ”Belts are bullshit, just train!” Or hedonism, “You are a 4-stripe pink glove, with a two-stripe white belt, and a red sash in clinch.” We may, and most likely are, simply avoiding and perpetuating the entire issue.

Instead I would like to address the issue head-on and realistically. Recognizing the fact that 95% of all human beings have been raised in a system, from grammar school forward that is based almost entirely on measurement from outside sources. As such, in order to help people see through that, we have to recognize it as it exists, here and now.

That brings up the question all coaches have to eventually ask themselves:

How do you measure?

I recently witnessed an interesting conversation between two BJJ black belts. One mentioned the recent promotion of an athlete that both instructors knew well. The one coach asked the one who gave the promotion a very simple question, “How did you measure?” With that simple question, the coach who had given the promotion became a little defensive. “You don’t think he deserved it?” “What are you trying to say?” Again, the reply came back, “No, I am just asking how you measured?” What a key question that is.

How do you measure?

People like to make lists. It is a psychological phenomenon, and the understood reasons for it are really interesting if you want to look them up.

Every field likes to rate itself, and every art form, sport, and craft opens itself to being measured the moment you share it with another human being. It is just what usually is. That being said, it is always interesting to see how people rate my own. By my own I trade, and by trade I mean teaching human beings to fight well.

When it comes to this measurement some people rely heavily on anecdotal evidence. This is often (not always), a popular one with traditional martial arts, JKD, and RBSD (reality-based self defense). I don’t think an analysis of why this type of evidence is worthless or, at best, an extremely poor form of measurement is needed here. I think most people will get that understanding first, which I believe helps create the question, “Hmm…is that really true?” to begin with. That is probably a thought already in surplus with those of you reading this now, and that is a very good thing.

After all, haven’t we all heard the stories of the eighty-Year-old martial arts master that levitated a car in mid air, or fought off half a football team with a tree branch? By now I have to assume we all know better than to take those stories seriously, so let’s move on.

Another popular method is how successful any single athlete from a gym is in a particular competition. This is a far better comparison then any form of anecdotal evidence but it does have one major flaw. It can only account for a few known subjects. These subjects may show a high degree of skill, and one can assume that they found worth in working with those coaches based on the fact that they trained with them. No doubt about that, but what about the rest of the gym? How are the average members (the other 95% of the group), doing in terms of performance? Can they bring game?

If not, I think it is a safe assumption that the major skill sets the successful athletes have do not come from that gym either. I base that on the fact that, if they had, then the rest of the gym would also show marked improvements in performance. Not at the same level as a pro athlete, of course, but as measured against his or her own, individual, past levels.

I say that because in a good gym everyone will grow as measured against their own past levels. This is a natural result of proper Alive training in a healthy environment. I know it for a fact because we do it daily here.

That brings me to the third measure of performance, and the one I would offer as the most accurate in terms of skill within the trade: the overall performance of the majority of students over a specific period of time.

When the majority all increases at a measured rate, then the training methods and coaching itself can be shown to be valuable.

In that kind of environment the athletes that want to take this to a high level in terms of competition will thrive. They will grow, fostered by a large community which serves as both a support base, as well as a good pool to draw from in terms of sparring and drilling partners. And the community itself will grow together at a steady rate.

As each individual grows better within a certain skill set they are able to bring greater challenge to their fellow members, and the whole class grows in terms of evolving game. It is a healthy, synergistic community.

It will, by its nature, be healthy and completely organic. It will grow at its own rate, with new members coming, and others moving on in time. It will contain a wider margin of membership, all ages, male and female, hobbyist, pro/am athlete, and everyone else who is built to try this process out at some point.

What if an organization (in this case a group of gyms which share the same training methods) could show that it had produced consistent performance in the majority of all its members, not just at a single location, but worldwide? Would that be an accurate form of measurement when it comes to evaluating objectively the training methods it uses?

Speaking for myself, I think it would be a good place to start looking.

To contrast that with the previous two forms of measurement, anecdotal and based on single individuals, I have seen very famous MMA and BJJ gyms that have produced noted competitors, and whose main cliental progresses slowly or not at all.

You will often find at these locations that the average members are viewed as either a paycheck, or cannon fodder for the more valued competitor.

I don’t mean to imply that there are not some very good gyms out there, but I would say that the majority of the well-known ones I am very familiar with would fall into the above stated category. It is very, very common scene. I travel around the world and hear from all sorts of people who share with me their negative stories about training at such gyms.

Regarding the anecdotal schools, let’s just say that we are talking about an apples and oranges comparison here. There is no point including them.

Let’s call this above stated conclusion the value of ‘community‘, and we will get back to it and exactly why I feel it is so important when it comes to BJJ belts later in this article.

How do you measure?

I have given this subject a lot of thought, and here are some of the perspectives I hold on this topic.

Technical performance is the sole measurement I use when awarding BJJ belts (with the exception of higher belts that may teach, at which point coaching skills also become critical). It is a conversation I always have with the athletes before and after any belt evaluation I give.

What I say simply is this, “You can be a tough fighter without being technical, due to aggression, size, explosiveness, strength, etc., but you cannot be a good technician without being able to fight. It’s impossible. What I look for is a good technical skill, as by my definition of “technical”, both personal performance, and overall technical ability within the skillset of BJJ is contained.

As I observe an athlete against various opponents, I notice if they are patching up weaknesses in their own game, technical holes, areas where they may be lacking some core fundamental skills, with superior attributes. If they are, they have to be willing to shelve their own ego long enough to stop doing that so that we can see what’s left. What is left will be their technical game.

Think about it, if you can rip out of an arm bar using explosiveness and speed, or escape a triangle by picking up your opponent, or escape bottom by bench pressing the person on top, should you?

The answer depends on the context, of course, but I would offer that for most people most of the time, the answer is an obvious no. Within the gym you want your training to be as technical as possible. If you are getting caught with arm bars, we want to find out why and then develop a technical solution that will work against larger and stronger opponents. This way, when you find yourself matched against a bigger, stronger, faster opponent; you will still have game.

Although we want all of our classes to be athletic, and to push our limits to some degree when we train, we also want to make equally sure that we are training in an intelligent and highly technical manner.

That being said, as a BJJ coach I am not there to measure how fast a person can sprint 50 yards, or how strong or explosive they are. I am there to measure technical skill within the core fundamentals, the basics; of the delivery system we call Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu. That is what I do.

How about Competition?

Competition is great but, as coaches, we have to remember this: you can’t really get a feel for someone’s technical performance based on a single competition. One time performance in a competition is not an accurate measurement.

Having stated that, let me be clear, I do think there is value in the journey that is preparation for competition. Getting in shape, becoming stronger, faster, and more explosive, tightening up your game, facing the nerves, thoughts, and pressure that exist in competition. For those meant to take that journey, it is a wonderful learning experience. So that’s not the question.

The question is, would a one-time performance accurately measure an athlete’s technical skill level within BJJ? My answer isno.

First, no single performance can measure that. Only multiple performances over a wider period of time, against multiple athletes, would.

A single performance could easily be related to a super high level of conditioning, which as I stated above, is not what I am paid to measure. Unless I see the athlete on a regular basis, or observe their progress in a series of competitions over time, I need to have another way to evaluate performance as a coach.

I also want to point out that not everyone wants to, or needs to, compete.

If I, as a coach, make public competition the sole criteria for measurement I use, then I leave out a huge percentage of people who might find tremendous value in BJJ.

In addition, I think the teachers or coaches who try and tell others that they “Are not living up to potential” or other such bullshit, need to find new jobs.

I have written before about the poison teachers, but suffice it to say that it is never our job to tell others what they should be doing with this art form. Some may just want to roll, or move, or play. That is exactly as it should be.

By the way, everything I just stated above can equally apply to any single day event and that would include, of course, a visit to a new gym.

We often have blue and purple belts walk into our Portland gym from other schools. Sometimes they do exceptionally well with the athletes on the floor because they are bringing a type of game that people there are not used to.

Sometimes they do really poorly because the athletes at the gym are bringing a type of game that they are not really used to.

In short, as a coach, I have to tell you that it is honestly hard to say where a person may be at in terms of performance when they only visit my gym for one or two evenings.

If that same athlete stays at our gym for a week or more it becomes much – much easier to evaluate their game. The other athletes start to get a sense for how the person moves, likewise they get a sense for how the gym regulars move, and it becomes far clearer for me to observe what strengths and weakness that athlete may have within the game.

The black belt trap:

The last type of measurement I will talk about is a trap that I think some coaches can fall into with BJJ, and that is when you begin using yourself as the yardstick.

Besides the obvious issue of being too small a sample to gain an accurate measure from, there is the issue of “style“. Each athlete in BJJ, and each black belt, has their own type of style or game. Some styles will match up better then others do. This is a fact not just with BJJ, but also with all sports and competitive activities.

As an example, I may crush someone when rolling or tap them quickly several times over. Is that a good measure of where their game is? Not always. Sometimes I may just be having a ‘good day’, and they are just having a bad day. Other times it is simply a question of my style, which may match up really well against the way they play.

Likewise, if someone gives me a very hard time that does not automatically mean that they are at a certain level within BJJ. Again, it may just be a poor match of styles, or I may be having an off day.

That being said, the temptation is to use ourselves as yardsticks by which we measure our athletes. I believe this is a temptation of the coach’s own ego and this is not fair to them, or to us.

As we age our performance skill may start to decrease a little. This is part of the process of being an athlete and a coach who participates in the game. It is, in my opinion, a positive part of the journey that we all must face in time. If we are using ourselves as the yardstick then the entire performance standard will begin to slip as well, and that is one of many problems that comes with this form of measurement.

This is why using yourself as the primary yardstick for evaluating others is never a smart coaching method.

It is about community:

Again, we come back to that word. When it comes to measurement, all the above stated dilemmas become easy to solve with one word: community.

A gym which has a large body of committed athletes, different sizes, different types of games, etc., all of whom are training together in an athletic environment, is by far the best way to measure any single individual’s game.

On this mat you stand as a blue belt, or on this mat you stand as a purple belt, is easy to say when you see that athlete, work with that athlete, and roll with that athlete, week after week.

With that in place, competition becomes a great way to test the overall training environment of the community itself.

By that measurement SBGi comes out with flying colors. Time and time again our athletes all over the world have shown the ability to enter grappling and MMA competitions and do fantastic, event after event.

This shows two things:

First, we have great training methods.

Second, I have never compromised on the standards that we have held for SBGi. No matter where I travel in the world, the measurement for performance has remained solid.

Letting it grow, letting it go:

It is true that there have been people who have become frustrated with our very strict performance standards. A few have even left the organization because I have refused to award them a belt, which they felt they were obligated to. That is exactly as it should be. Also, it serves as a positive sign, which points to the fact that we have held true to our standards.

I have not, and will not, award a belt because someone is my buddy, or because someone is a well-known coach, or because someone has been around SBGi for some period of time.

Simply put, I will not compromise on the process. I never have, and I never will.

I will only speak for myself in the last part of this article. Since I still head up SBGi, what I am saying speaks for our association as well, as related to those people I have given belts or certificates to over the years.

I have maintained extremely high standards of performance for the coaches and athletes I have recognized within SBGi.

I have run my own full-time gym in Portland Oregon for well over twelve years, and, in the last ten plus years, I have taught seminars and coached athletes all across this beautiful planet.

In that time I have only awarded thirty or so purple belts, two brown belts, and one black belt. In terms of SBGi coaching staff I have awarded seventeen coaching certificates, of which fourteen have continued working through SBGi, one went on to create Team Quest, and two others went on to pursue other things.

My point is pretty simple. I have taught hundreds of seminars, in all kinds of locations, and had thousands of students come through my doors, many who have stayed for years. In all that time and travel I have recognized, personally, less than twenty coaches and awarded only two brown belts.

It would have been very easy for us to accumulate a truly massive list of instructors worldwide.

If our standards were simply a matter of sending an e-mail, buying a membership, attending a class, hosting a seminar, or taking a weekend instructor’s course, we would have hundreds of coaches by now. For a variety of reasons, I set SBGi up in such a way as to ensure that all our coaches, regardless of where they are found around the world, hold an unusually high level of performance and teaching skill.

If you pop into a gym in Ireland, The UK, Denmark, Canada, NY, FL, or any other SBGi location within the USA or world, that reality will become self-evident.

As I wrote about in the last entry, my main intention as a coach is to HONOR THE PROCESS. Honoring the process sometimes means seeing a friendship through the conversation, “No, I can’t endorse that,” or “No, to measure you for this belt I need to see you on the mat against other athletes of that rank”, and should they refuse that criteria or move on from the organization because those standards are maintained, then letting them walk away and learning to be at peace with that, is part of what honoring the process means for us as a coach.

It is all part if our journey, our trip, our chance to grow as humans.

What is the point?

Only the evolution of the art itself; what transcends individual attributes, and individual personalities?

In the end, what is passed on?

What stays and gets transferred?

For the organization, as a whole, to grow, the next generation needs to surpass our own, and what makes that happen is the conceptual understanding of the technical game that gets passed on, and then built upon, by the younger generation. The big picture is regarding the physics, base, and movement. All of that becomes lost if we begin measuring who can run the fastest mile, or takes the best punch, or lift the heaviest weight within our generation.

This is, in part, the reason for the emphasis on quality of technique that I look for within our organization.

Is it healthy?

A good father doesn’t try and control his son’s path, choose his son’s path, or push his son into a particular path. A good father is like a good coach. He acts as a guide, allowing his son to take his own journey and pursue his own bliss.

A good father, like a good coach, expects that his son will surpass him. To one-up him so to speak, that IS the evolution of the consciousness.

As a gym we seek the same. Each generation of students becomes better, at a faster rate, than the generation before.

Looking at SBGi, this is absolutely shaping up to be the reality, and I for one, am glad to see it happening.

The expression of that value set community-wide, is a good measure of whether or not we are a healthy group. I will tell you that, right now, we are glowing.

Integrity, the SBGi way.

It’s about honoring the process. If you get a belt from me it will not be given because we are friends.

It will not be given because I want to do seminars at your school.

It will not be given because you have trained with me for fifteen years and, therefore, ‘deserve‘ it.

If you get a belt from me it will be because you have reached a level of technical performance skill within your own game that you can also articulate to others.

It will be just a symbol, of course.

Make no mistake, it symbolizes something tangible, something real, and something meaningful in terms of measurement within our craft of BJJ, our trade of fighting.

It will be given with absolute respect and care, and it will be valuable because it was something that could never be bought, bargained, or traded for.

It will be something personal, from me as a coach, to you as an athlete. In that sense, it will mean a great deal to me at the time, because I will be proud of you, and happy for you.

If, within this process, you become a BJJ black belt within our organization, and you maintain those same standards, then you too will be honoring the process. That will be our tradition at SBGi.

It is about authenticity; it is about love for our members andhonoring that process.